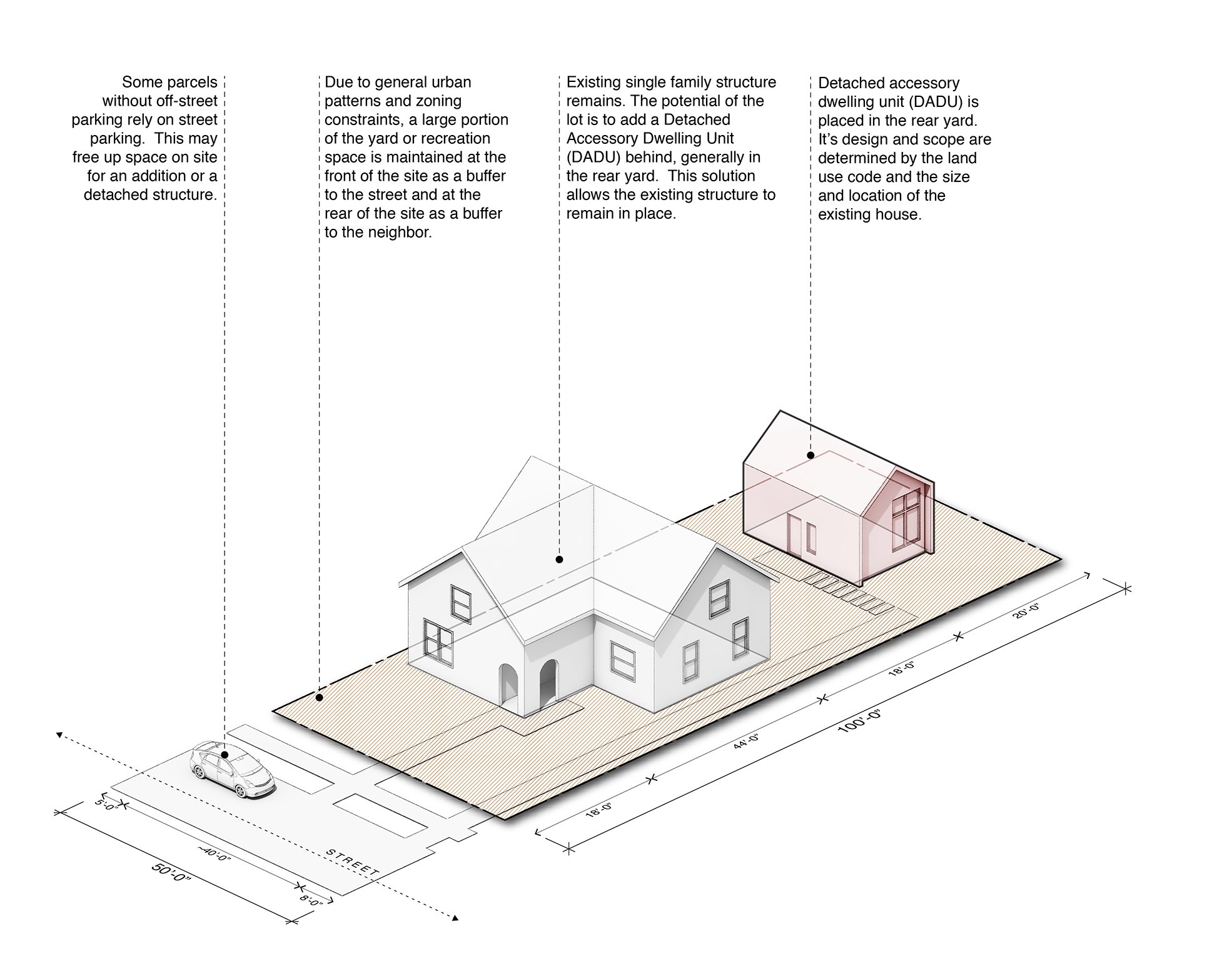

As part of its plan to increase housing options in the city and to find solutions to solve missing middle housing, the City of Seattle has recently changed regulations around accessory dwelling units. Commonly referred to as a mother-in-law apartment, an accessory dwelling unit is a smaller residential unit tied to a single family house that comes in both an attached and detached typology, known as ADU and DADU respectively. Picture a finished basement with its own kitchen and entry from the rear or a separate cottage on the same property.

In previous years, the Seattle Municipal Code enforced by the Seattle Department of Construction & Inspections (SDCI), required two significant items that dramatically reduced the feasibility of ADU or DADU projects. One, each ADU required onsite parking be provided, and two, the property owner would have been required to physically reside in one of the units on the site for at least 6 months out of the year. In addition the units were limited to 800 square feet. The former requirement ate up valuable footprint space making a lot of Seattle sites, especially those with environmentally critical areas like slopes and wetlands, too small to add an additional structure, and the latter often priced out any developer beyond a homeowner interested in taking on construction risk to invest in their property. In 2019, the City of Seattle removed these requirements and began allowing two ADU’s per lot. Since then Seattle has seen an increase in this type of project entering the permitting process.

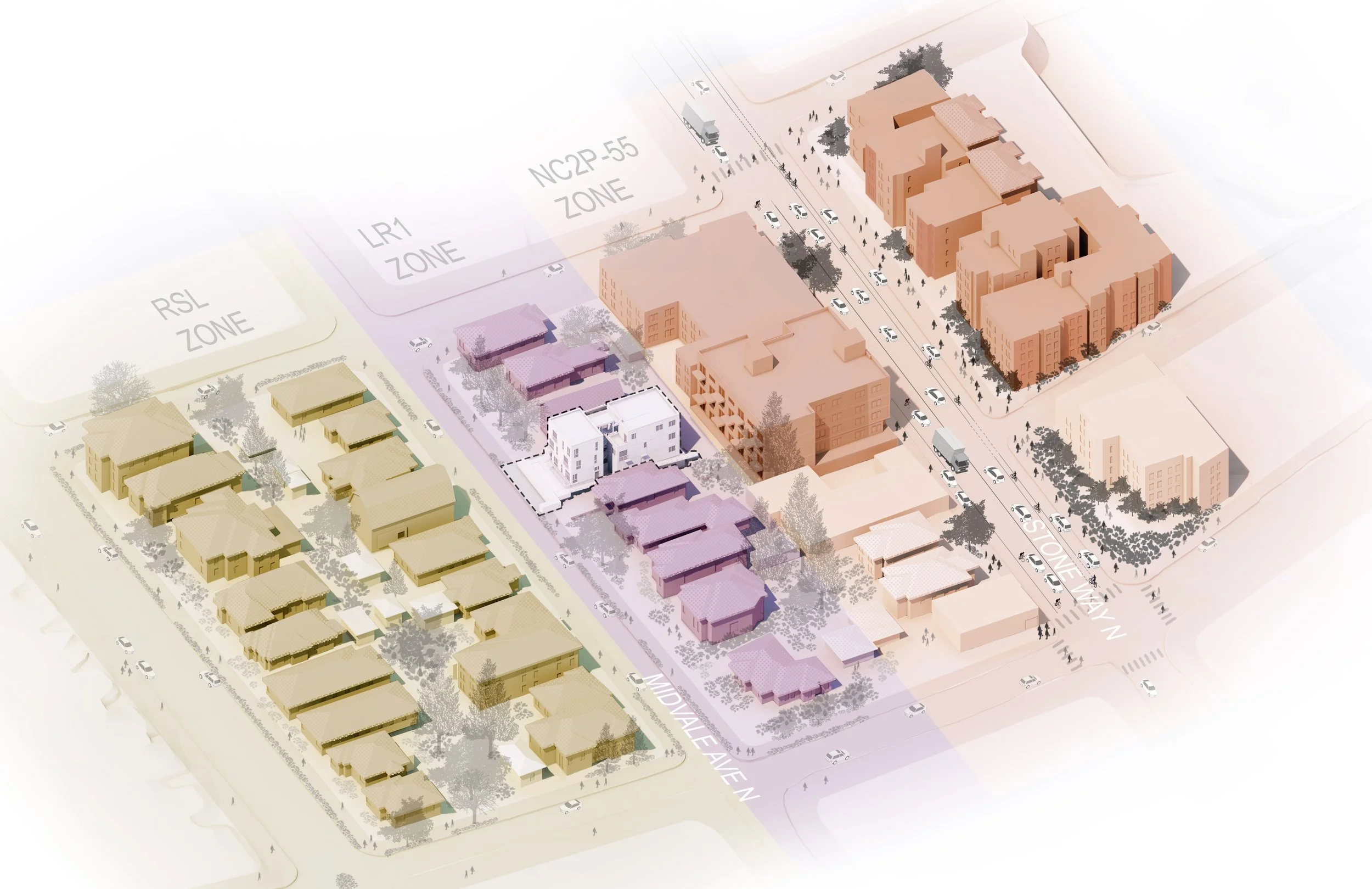

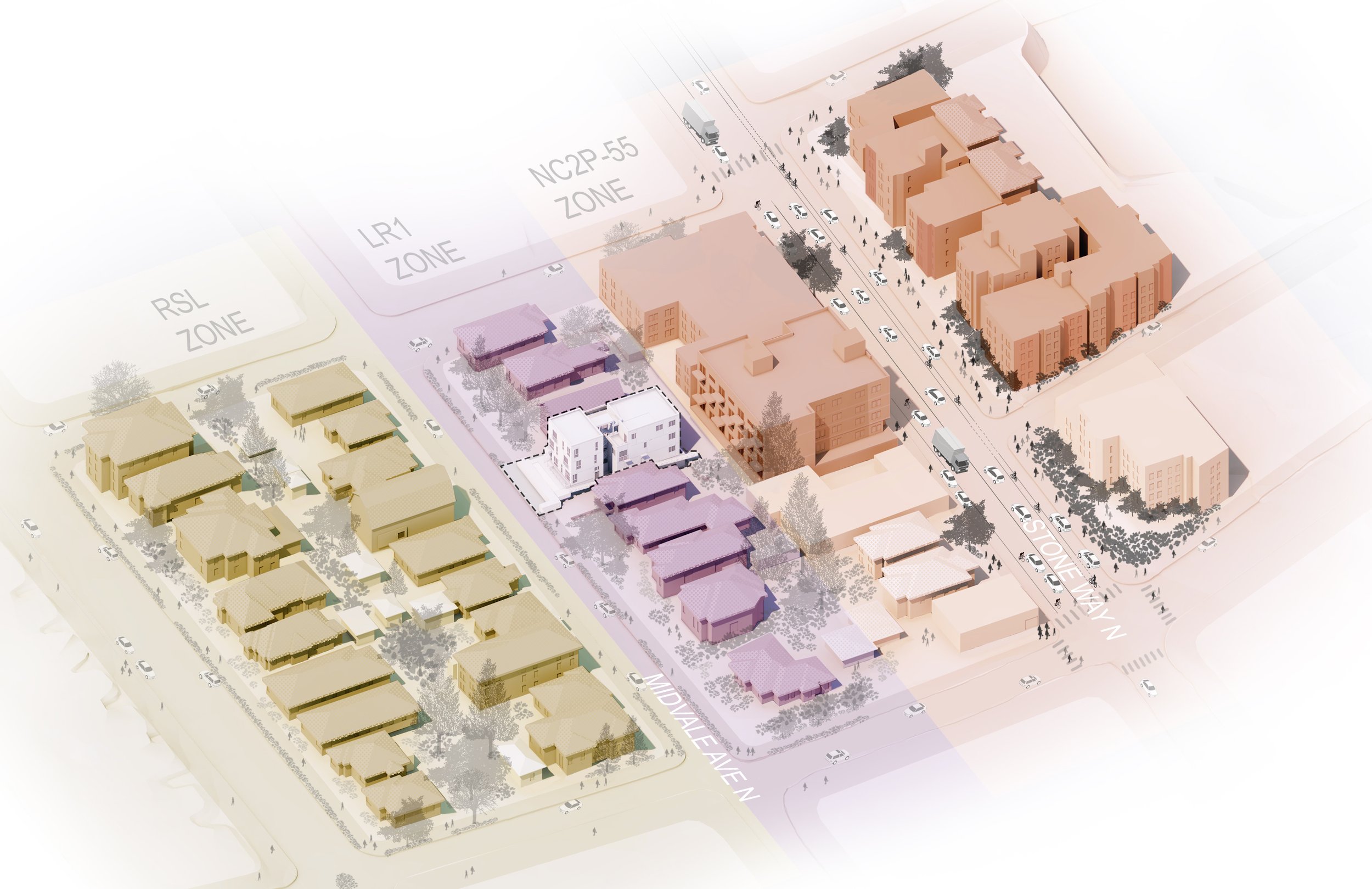

While this change definitely encouraged the development market to explore another avenue to create housing, the ADU/DADU cluster has very little difference to a project type we at b9 architects are already familiar with; namely, the duplex and Single Family house, or even a three unit townhouse development. Where the two differ most is in zoning and size.

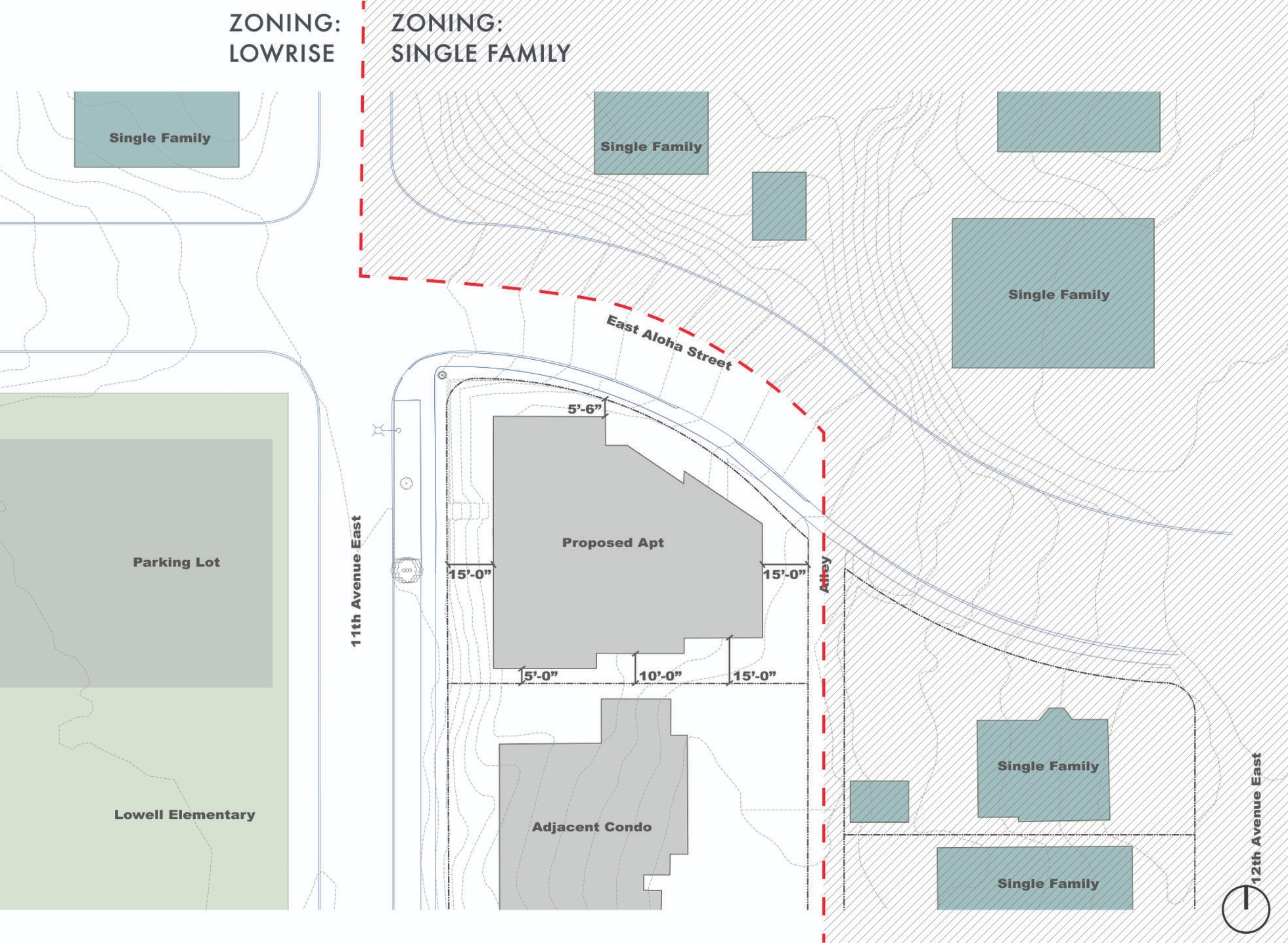

As a part of the change to the municipal code that allowed this type of project to flourish, the City has made this three unit typology admissible in all Neighborhood Residential zones (formerly Single family residential), a zone that until this change could only allow one house with one accessory dwelling unit. With this change, a significant portion of land in the City of Seattle has been unlocked as developable. The trade off is in size. While Seattle’s multi-family zones would allow three townhouses of any size (so long as they meet FAR guidelines) this typology limits an ADU or DADU to no more than 1,000 sq ft each, with allowances for storage and garages that exceed that amount.

The 335 DADU is a small backyard residential unit completed in 2017. This would have been the only typology allowed in Single Family zones.

The 335 DADU is a small backyard residential unit completed in 2017. This would have been the only typology allowed in Single Family zones.

If you look at our 2018 study Urban +, you’ll see how the backyard building can range in size and scale based on the lot number, size and zone. In 2018, the only thing that could be done with a single lot in the Single Family zone is what you can see in our 335 DADU project. Since the code changes, the new type of project could resemble the configuration of several of our completed projects, including Urban +, Urban Share, or the North lot in Row 1412. In 2022 we used our expertise in Urban + to help two of our clients approach this type of project.

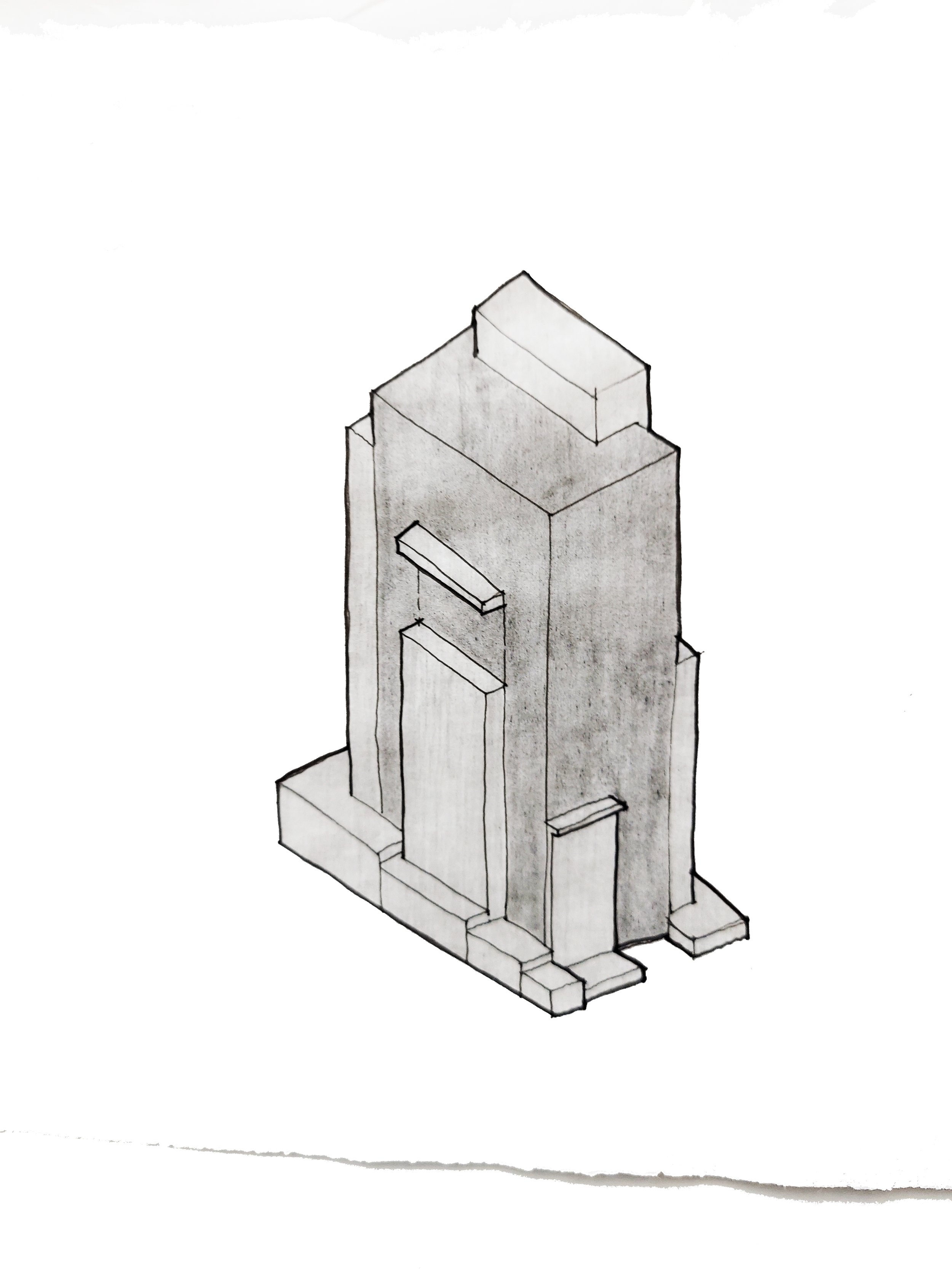

An axon of the 335 DADU. This project could add an additional ADU based on new requirements.

An axon of the Judkin’s Park House. This configuration would not be allowed in Neighborhood Residential zoning due to the location and size of the two homes.

An axon of the Urban Share project. While it’s three units, this configuration would not be allowed in Neighborhood Residential zoning due to the location and size of the two homes.

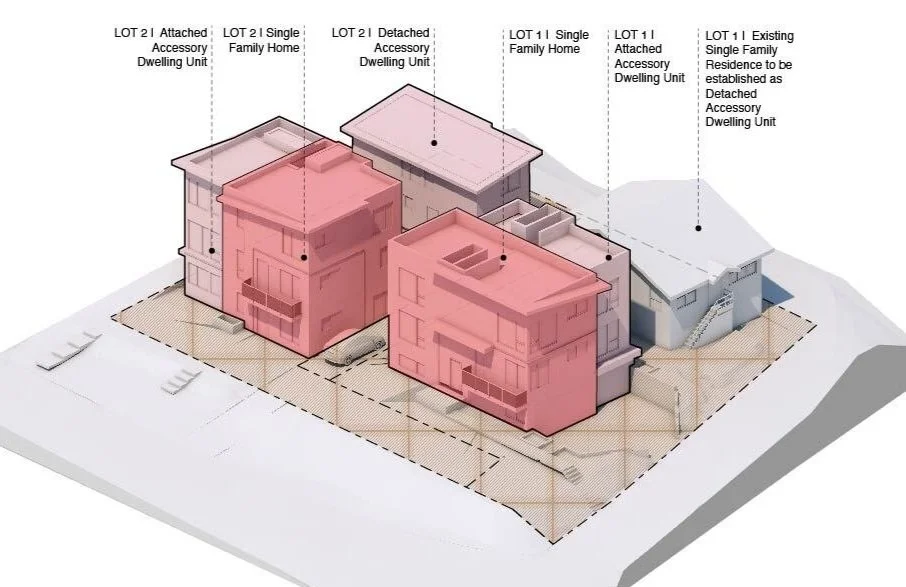

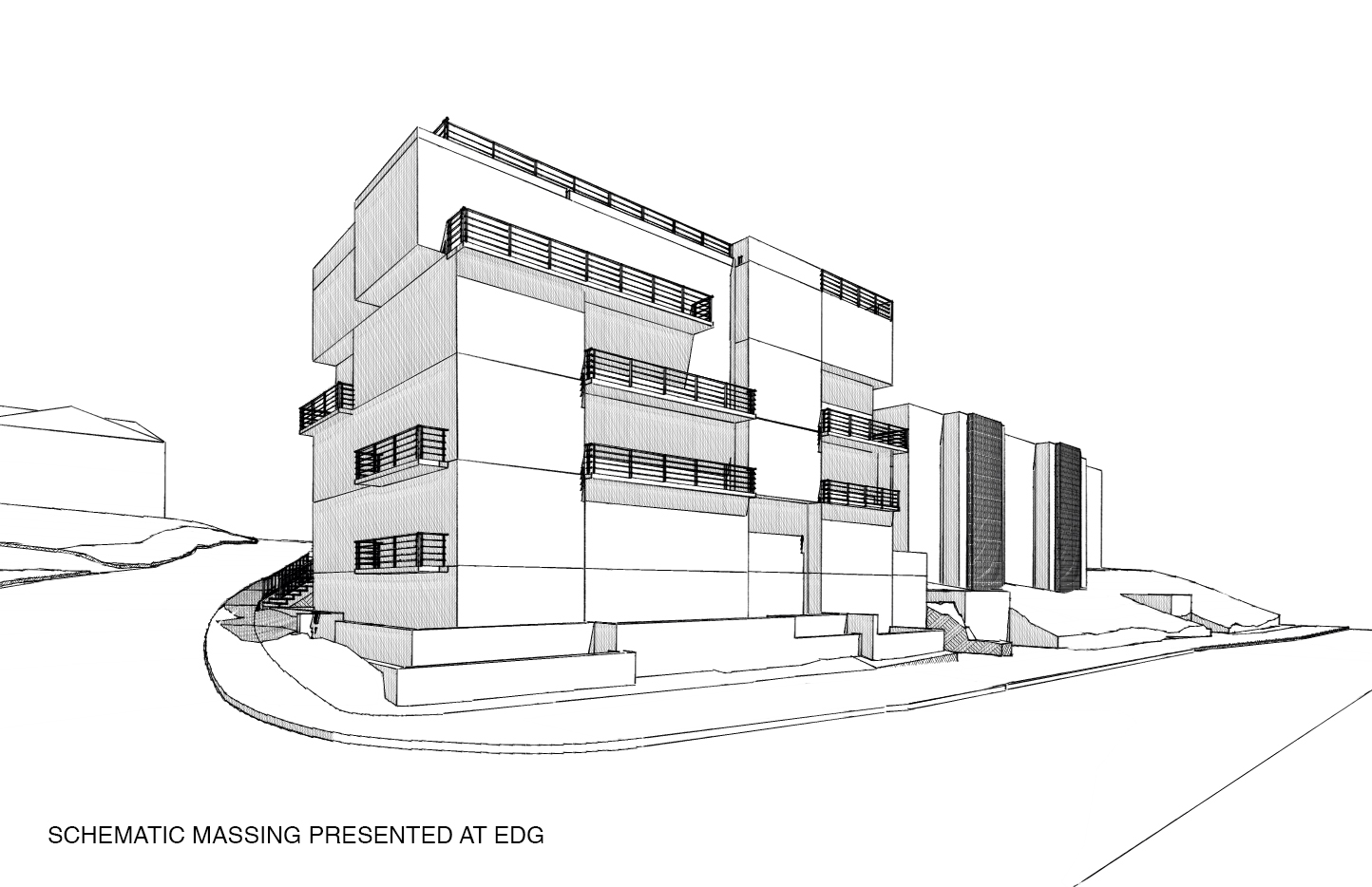

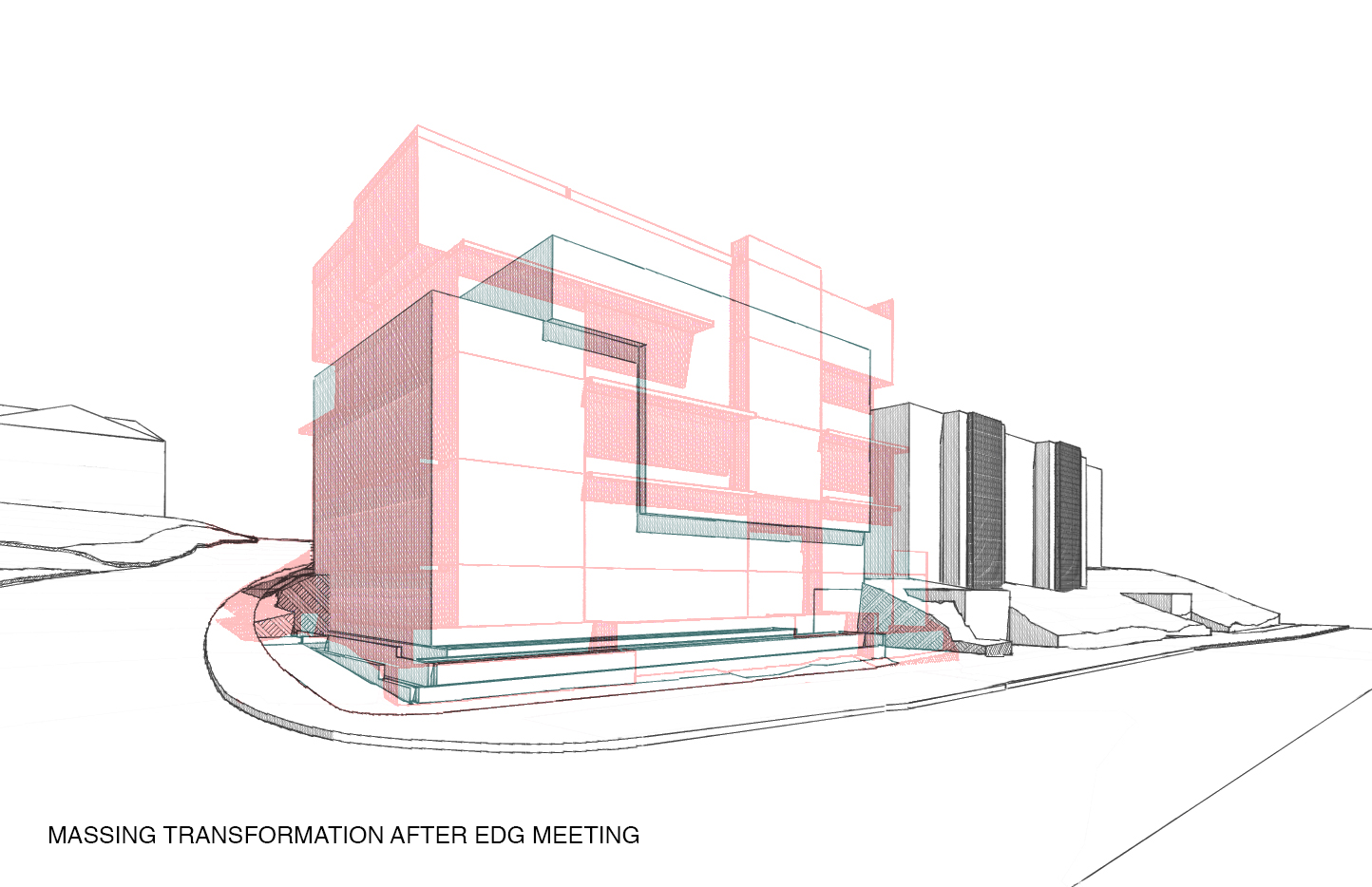

The Genesee ADU Cluster in West Seattle will add five residential units across two sites of current single family homes. One of these primary residences will be retained and converted to the allowable DADU for that lot. The other existing residence will be removed to make room for the new dwellings. The duplexes (or Single Family w/ ADU) that face the two streets are three stories with living on the second floor. Each new unit has at least two bedrooms, with the two larger units designated as Single Family Houses having three bedrooms. Similarly, in our project Urban Share, a Single Family home remained on site while a duplex was built behind it. If Urban Share were on a Neighborhood Residential zoned lot today, the two small units in the duplex would be comparable in size to what is allowed now as an ADU or DADU.

The Genesee ADU Cluster retained an existing Single Family House.

Due to being a corner site with access to two streets, we are position the existing Single Family house behind a new structure, and designate it as the site’s DADU.

The site plan for the Maple Leaf ADU Cluster is organized to give each of the three units a private outdoor space. While each of these spaces is accessible to all three units, they are recessed from the street and are configured like a checkerboard with each unit exiting through a rear door onto an established space. Due to the new code allowances, parking is only provided for the front Single Family home in a ground floor garage.

In the end, the driving factor for the large increase in ADU and DADU development in Seattle is cost, specifically related to the process required to obtain a permit for construction. These three unit projects, while being similar to a three unit townhouse project, are not required to participate in the city’s Design Review program, or comply with the requirements of the Mandatory Housing Affordability program. This streamlines the entitlement process, and saves money while being more predictable. While this will help bring the much needed residential units to the area, it will increase the amount of small ADU and DADU units that come to the city, which offers a more affordable option in the market.